How to Restart Your Season After a Break

3 steps to ensure your second peak is higher than your first

by Chris Bagg

Hey! You listened to us after our last article and you took a break. We are proud of you. Taking a break is tough as an endurance athlete, we get it. Each day off feels calamitous, as if your fitness is fading away forever. Many athletes know intellectually that a quick loss of fitness isn’t actually the case, but there is a huge difference between knowing that intellectually and being able to keep an even keep, emotionally. As we said in that article, taking a break will often allow you to reach a higher level of fitness in the second half of the season than you achieved in the first, because you will be able to accomplish your sessions with more focus and energy having taken some rest and cleared away any impending causes of burnout. The best way to think about this is that Fitness Fades Slowly but Fatigue Fades Faster. I guess that’s FFSFFF, or the sound tires make when they deflate in comic books.

But what do you do now, having taken your break and focused upon the remaining events of the season with renewed energy and enthusiasm? Many athletes start a bit too hard and get tired again right away. One sensible approach is to repeat the structure of your season up to this point, but in shorter phases. When building towards your first peak of the year, you probably divided the season into sections, first tackling aerobic conditioning or endurance, then working on a particular weakness (speed, VO2max, technique, or threshold, most likely, but it could be something else depending on your particular athletic makeup) before turning to race-specific preparation. Clearly you don’t have the same amount of time to prepare, so you’ll have a short mini-season before your last racing block to this year.

We’ll use an imaginary athlete today, who has just wrapped up their mid-season block, and is aiming for an fall Ironman. Maybe it’s Kona, maybe it’s California or Florida or Arizona. Let’s use Kona for our example. There are about 9 weeks remaining before the Ironman World Championships in Kona this year. Our athlete is a bit of a diesel engine with great endurance but may be slightly limited in speed, but we’ll want to make sure we assess that correctly before planning a whole bunch of workouts. Regardless of athlete type, however, we’re going to start back with two weeks of primarily endurance and middle-intensity interval training (remember that “threshold” is middle intensity!) before taking a week where volume drops a little but intensity drops a lot. This pattern allows us to focus on the biggest determinant of performance for ALL endurance athletes, which is volume, while also preserving the athlete’s ability to work on intensity in our second block. Here’s what the whole progression (for this particular athlete, remember) will look like:

Endurance Block (three to four weeks)

Testing/Speed/VO2max Block (two to four weeks, depending on athlete)

Race specific block and sharpening period (three to four weeks, depending on how long the second block was)

Endurance Block

An endurance block is, well, what it says on the tin. The goal of an endurance block, after a race, is to bring blood volume back up, get the heart tissue moving again, re-establish your routine, and begin building fitness/endurance adaptations again. When you take a break, your body sees that it doesn’t need as much blood volume, so it starts getting rid of that extra material. Your body is amazing at saving energy, and it doesn’t like paying the energetic cost to keep stuff around that’s not being used, unlike your aunt’s storage unit. Your heart tissue, since it’s not being used as much, will stiffen up a little, too, and since your heart is just a very complex muscular system, it takes some limbering up to get it working again. These first two changes are why you will see higher heart rates after returning from a break. It is NOT because you have “lost all your fitness.”

The next goals, re-establishing a routine and building endurance adaptations, are what we are here for. Most blocks of your year should be endurance blocks, since this particular energy system is really the thing that will determine your performance. Threshold and VO2max blocks may get all the attention, but endurance training should comprise the vast majority of what you are doing. How vast, you ask? Pretty darn vast, like, 70-90% of your training. The whole 80/20 thing has gotten a lot of attention recently, but it’s nothing new. Go back and look at Arthur Lydiard’s training programs from the 1950s and 1960s and you’ll see that he basically invented polarized training—recently we’ve just given what he did a catchy name. Endurance training should be moderate intensity (4-5/10 effort on the RPE scale) and you should do a lot of it. How much in this block? That will depend, but it’s good to give away some kind of guidelines. Go back and find your biggest endurance week of the year thus far. That week should be around 80% endurance work, 15% recovery/technique, and maybe 5% on stuff like high cadence training (bike and run). Let’s imagine that our particular athlete peaked at 18 hours for that big endurance week. Subtract 20% from that for your first week of your endurance block (so 3-4 hours) for this first week. The second week should equal your big week, and the final week should be about 10% above that big week (so maybe 20 hours in this case). Hours are an OK way to do this, but you could track by training load, too, either TSS/CTL (OK, but not ideal) or something like Session RPE (much, much better). But really this should be more a guideline than anything very exact: make the first week back somewhat smaller than your biggest week, the second week about the same as your biggest week, and the third week a little more than your biggest week. That’s it!

Testing/VO2max/Threshold Block

OK, you’ve re-established your training routine and made the changes you need to make in your physiology to have a strong final block of the year. If it feels like endurance is still something you could build, then maybe you take an easy week and then repeat the process above (your final week is now the biggest week of the year, so use that week as your guide). But if you had a solid season of endurance work thus far, you can move on to whichever system needs work at this particular point.

But how do you know what that is? Triathlon poses a challenge, since we’re not just talking about a single sport. If you’re only a cyclist, you can evaluate your past races and your training to discover what needs improvement. If you’re a triathlete, though, you need to evaluate your strengths and weaknesses for three separate sports, plus strength training! That makes for a lot of variables. Keeping things simple, however, is probably your best bet here. Talk with your coach or examine your past racing and training and pick which of the three sports needs the most work right now. Evaluating your weaknesses can be as simple as seeing where you’ve been landing in your age group for each discipline in your past races. Top 20% of swim and bike but only in the 50th percentile for cycling? Boom—it’s time to ride your bike more. Do a quick analysis of your past performance and pick one sport on which to focus for this block.

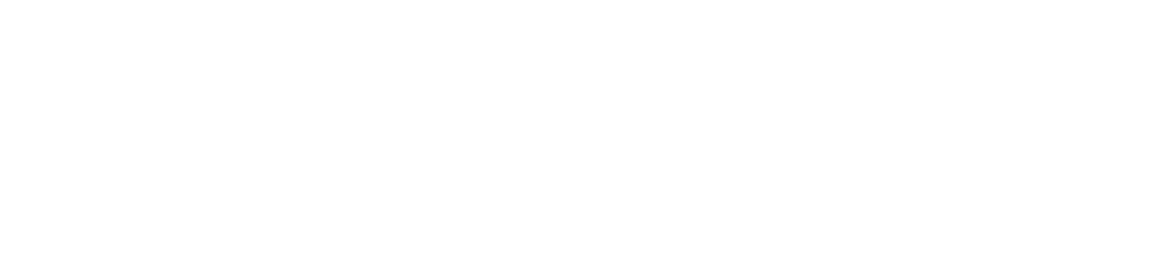

OK, now you’ve picked your sport, it’s time to figure out what needs to be done. At this point in the season, you’ll most likely be working on “speed” or “threshold.” Many coaches and athletes get the relationship between speed and threshold incorrect, and fixing that error can be the path to greater improvement. If your threshold speed/power (the speed/power you can hold for 30-70 minutes or so; the exact duration isn’t that important as long as it’s “long”) is relatively close to the speed/power you can hold for 3-8 minutes, then training your threshold won’t give you the biggest bang for your buck.

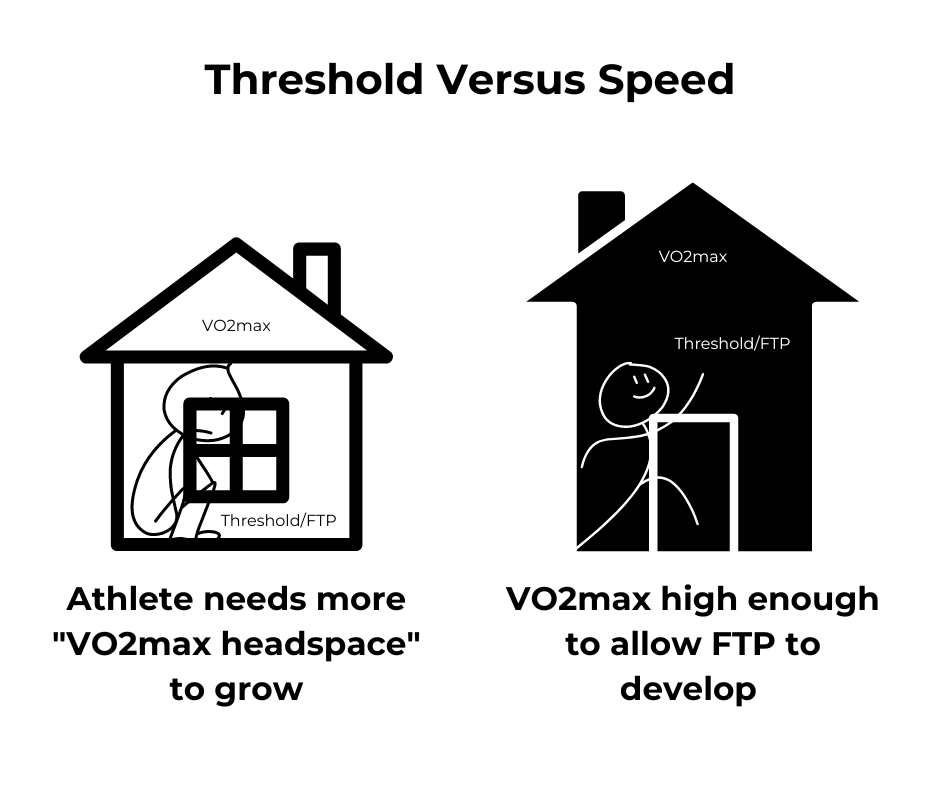

Let’s add some numbers to this whole shebang and give you some things to test. After your first 2-3 week endurance block, you should take 4-5 easy days to give your body a chance to rest and relax a bit before you do some testing. Whichever sport you’ve picked to develop, you’re going to ascertain your VO2max ability and your threshold ability. Whether we’re talking about swim, bike, or run, you’re going to do a shorter test (3-6 minutes, most likely) and a longer test (15-30 minutes, most likely) to figure out what needs to be focused on. Again, these are all rough tests—we don’t need lab equipment or really robust math, here, and the deeper into the weeks you get the worse off you’ll be. We just want a snapshot. So here are the different tests by sport you’ll need to do:

Next, you’ll need to convert your results into speeds (swim and run), most sensibly in yards or meters/second. Let’s give you some examples:

Fast Freddy swims 200m in 2:30 (150s), so his m/s = 200/150 or 1.33 m/s. Then Fast Freddy completes his 1000m time trial in 15 minutes (900 s), so his m/s = 1.11 m/s.

Steady Susan runs her 1200m in 5 minutes, or 6:42/mile pace or 4:10/km. 4:10 = 250s, so Steady Susan runs about 4 m/s during her 1200m test. When she runs her 3600m test, she does it in 15:30 or 6:56/mile or 4:18/km. 4:18/km = 258s, so Susn runs about 3.86 m/s.

Threshold Thomas averages 250w during his 30’ time trial, but only manages 295w during his 5’ all out test; VO2 Viola, on the other hand, holds 210w during her time trial but really hits that 5’ test, averaging 325w.

To figure out where we are, divide the longer test speed/power by the shorter test speed/power. This figure is the percentage of VO2max you can hold at threshold (roughly!).

Fast Freddy = 83% (1.11/1.33)

Steady Susan = 97% (3.86/4)

Threshold Thomas = 85% (250/295)

VO2max Viola = 64% (210/325)

OK! Now that you have these numbers, let’s give you something actionable. If the number is BELOW 85% (Freddy and Viola) this block should focus on threshold work in that particular sport. If the number is AT or ABOVE 85% (Susan, Thomas) you need to focus on speed/VO2max. What do these workouts look like?

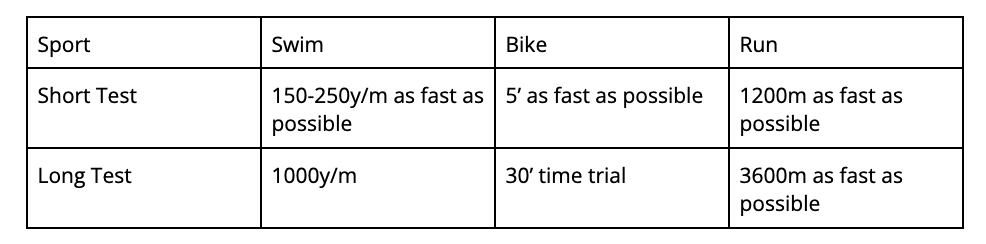

For threshold work, your focus should be on amassing as much time as possible in your threshold or FTP range, aiming to extend your time at those speeds and intensities, rather than trying to push FTP higher. So maybe you do two workouts in a week where you amass a total of 30’ in that threshold range, split into 2-3 intervals. Then simply progress the time in zone/range each week.

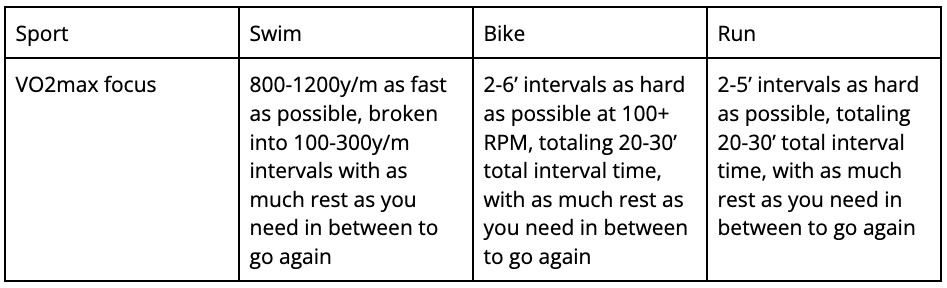

For VO2max work, your focus should be on working as hard as possible for 2-6 minutes, taking as much time as you need between intervals, and working up to 20-30’ of time in the range per workout, for maybe 1-3 workouts per week (60-90’ total time in range per week). You can probably do threshold work in two sports at once, and the other sport (probably your strongest sport) should simply continue the endurance focus of the previous block.

Please be careful with the VO2max work. It is strong medicine, and the run is where you can get hurt, so…be conservative! You’re working pretty hard during this block, so volume will probably come down a bit from the endurance block. Also, you can really only develop one sport at time with VO2max work, so just keep doing endurance work in the other two sports so you are fresh enough to hit the VO2max work.

Race Specific Block

The race specific block is pretty simple: extend the time you spend working at race-intensity intervals while tapering the volume in a sensible manner that allows you to arrive at the race both sharp and rested. Let’s imagine a four week race-specific block that has followed a four-week block that featured three weeks of VO2max development and a recovery week. The taper might look like this:

Week One: 90% of biggest endurance week, but include 1-2 sessions per sport per week that includes race-specific work.

Week Two: 50-60% of biggest endurance week, but include 1-2 sessions per sport per week that includes race-specific work.

Week Three: 70-80% of biggest endurance week, but include 1-2 sessions per sport per week that includes race-specific work.

Week Four: Race week and 30% of biggest endurance week, but include 1-2 sessions per sport per week that includes race-specific work.

Let’s use our example athlete to make this real. She hit 22 hours in her final endurance week, so the pattern would like like:

Week 1: 20 hours, 3-6 total sessions that include race pace work

Week 2: 11-13 hours, 3-6 total sessions that include race pace work

Week 3: 18 hours, 3-6 total sessions that include race pace work

Week 4: 6-7 hours, 3-6 total sessions that include race pace work

We can already hear you: “How MUCH race pace work?” Well…it depends! Remember that even at this stage, endurance work is always your bread and butter, so that should take up 50-60% of weekly volume. Recovery work should take up another 10%. So that leaves us 30-40% of the week can be race pace. So for that first week, the athlete might do 10 hours of endurance work, 2 hours of recovery work, and 8 hours of race pace work spread out over three sports. But this athlete is training for an Ironman, right? So race pace work is…endurance work. Maybe it’s “slightly harder endurance work” or 5-6/10 effort instead of 4-5/10 effort. If an athlete was training for 70.3, these numbers would be lower. Using the basic breakdown of 50% bike, and 25% each on the run and swim, out of those 8 hours we’d be looking at 4 hours of bike race pace and 2 each for the swim and run. That’s not too excessive!

CONCLUSION

As with anything like this sort of advice, please take this all with a grain of salt. Working with a coach is the best way to develop this kind of plan. A coach knows who you are and what you can handle, and will be able to prescribe how all of this works. If you’re self-coached, remember that being conservative and doing slightly less than what you think you can handle is always a good plan, and if you’re in doubt, you will never go wrong with just doing endurance training (or, at least, you’re unlikely to do harm).

If you’re interested in learning more, book a consultation with us!