If the Internet is to be believed (a dubious statement, but hey, it’s what we’ve got), then somewhere between 37% and 91% of triathletes will be injured in the coming year. Exact numbers for triathletes elude detection, but we can tell you that the old cliché around triathlon being safer due to “spreading out the stress” does not hold water. So what’s an endurance athlete with a multisport habit to do?

First of all, let’s define our problem. Two different types of injuries dominate running and triathlon: acute and overuse. Happily, acute injuries occur less often than overuse, but often require a full cessation of training. Acute injuries include sprains, muscle strains, abrasions, and drastic injuries such as broken bones. Overuse injuries show up much more often (about 80% of total injuries), and these happen when there is a mismatch in stress (your training!) and the strength of the tissue. You exert too much stress on some part of your anatomy, and eventually it gives up, like that paper clip in Spanish class you bent back and forth until it snapped. Acute injuries, although they seem terrible, probably present a better situation for the endurance athlete: you’re forced off your feet, and can’t hurt yourself any more until you heal. Overuse injuries, on the other hand, can be career-enders; they creep into your life slowly and then never leave. To make matters worse, runners and triathletes morph into their own worst enemies, pressing injured tissue back into service too soon. So let’s fix the problem and keep you healthy forever!

Past Injury Leads to Future Injury

If you’re already injured, you’re like “thanks, bro, you could have told me that before I stress fractured my femur,” but we can’t stress this enough: if you’ve been injured before, you’re more likely to get injured again. That fact, however, isn’t a death sentence. The odds aren’t in your favor, but by being smart you can improve your probability of staying healthy, and that’s really all that injury prevention is: shifting the odds so that they are more in your favor. If you’ve been injured before, everything we’re about to tell you counts double. If you’re injured right now (usually the time athletes find articles about being injured is when they’re, well, injured), then don’t despair. Two things will improve your odds moving forward: first, whatever your program of rehabilitation defines, stick to it with the tenacity of hanging onto the lead pack in a race. Diligent rehab strengthens the weak tissue that failed you in the first place, and injury can be the wakeup call an athlete needs to fix the issue once and for all. Second: return to training slowly. We’ll get into this below, but if you take an injured athlete and return to training too quickly, you are doubling down on your risk factors. Since you’ve been hurt, you’re already at risk—why would you make it worse by pushing your return?

Running is Likely the Problem

Although this article is titled “how to stay injury free in triathlon,” it should really be titled “how to stay injury free while running for triathlon.” The number of running injuries in our sport dwarfs those of swimming and cycling. Here is a short list of risk factors that could raise your probability of injury while running:

Previous injury (see!)

Using orthotics/insole inserts

Too much volume, too soon (see below)

Running more than six times per week

High number of years in the sport

Low number of years in the sport

Movement dysfunction in any of the sports

Too low volume (we’ll cover that, too)

Menstrual cycle abnormalities

Past participation in only non-load bearing sports (swimming, cycling)

Racing more than six times per year

If you have any of these risk factors, you may be at risk for a running injury. What’s a “high number of years in the sport?” We’d call that more than five in a row. What’s “low”? Less than two, most studies seem to suggest. Two other factors (too much volume, or too little volume) we’ll cover next.

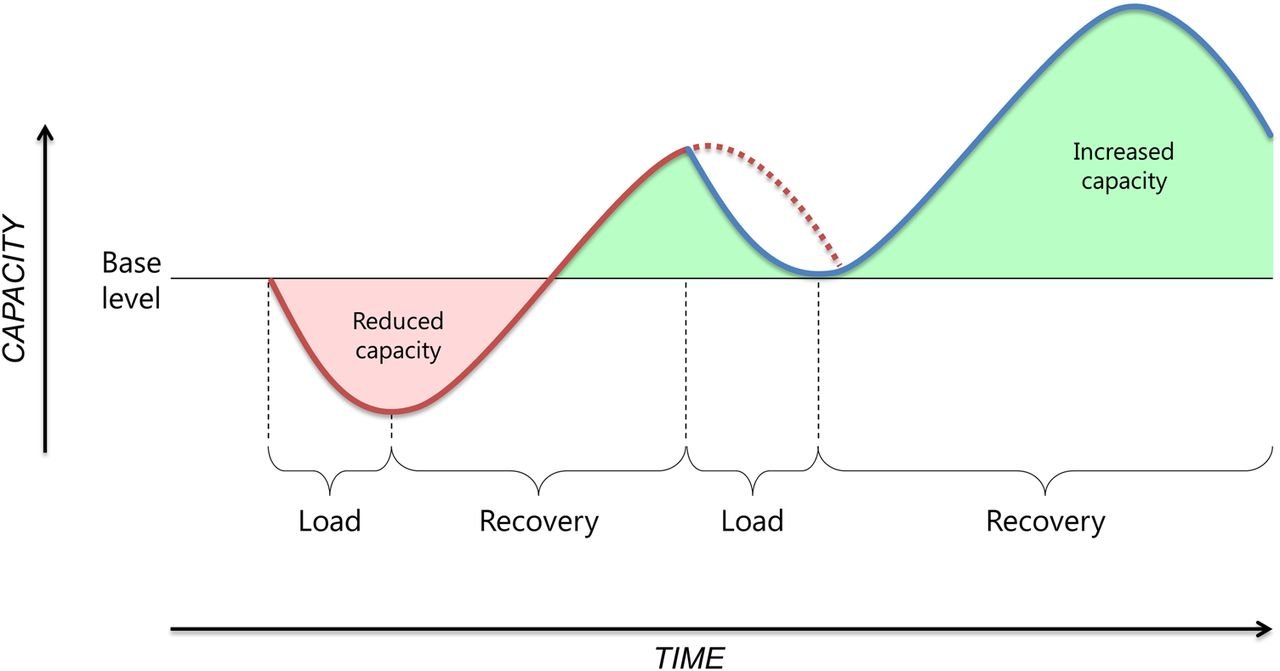

Ramp Rate and Recovery, Rather than Total Load, Predicts Injury

Remember what creates an injury in the first place: more stress on a tissue than it can bear. When we perform any kind of repetitive motion, we make demands on our anatomy: the muscles, bones, tendons, and ligaments of our legs, core, and lower back power our cycling and running, while our shoulders, lats, core, and hips drive our swimming. All of those structures require slow reinforcement in order to function properly. Ask too much of them too soon and they break. The pain you feel while injured is your body trying to force you to stop performing the stress that created the injury. In order to avoid overly stressing your training tissues, you need to give them just the right amount of load (not too much nor too little) to strengthen them. How much? Well, that is the industry-wide question, isn’t it? While we can’t give you an exact number, we can provide you a helpful visual:

Proper training loading

Above, our athlete loads and unloads his body properly, resulting in greater ability through the principle of progressive loading: you stress a system and then let it rest, allowing it to build back better than before. Then you stress it again and rest it again. The result? Greater ability to perform the movements in question, with a lower degree of injury risk. What happens when we apply too much stress and not enough recovery?

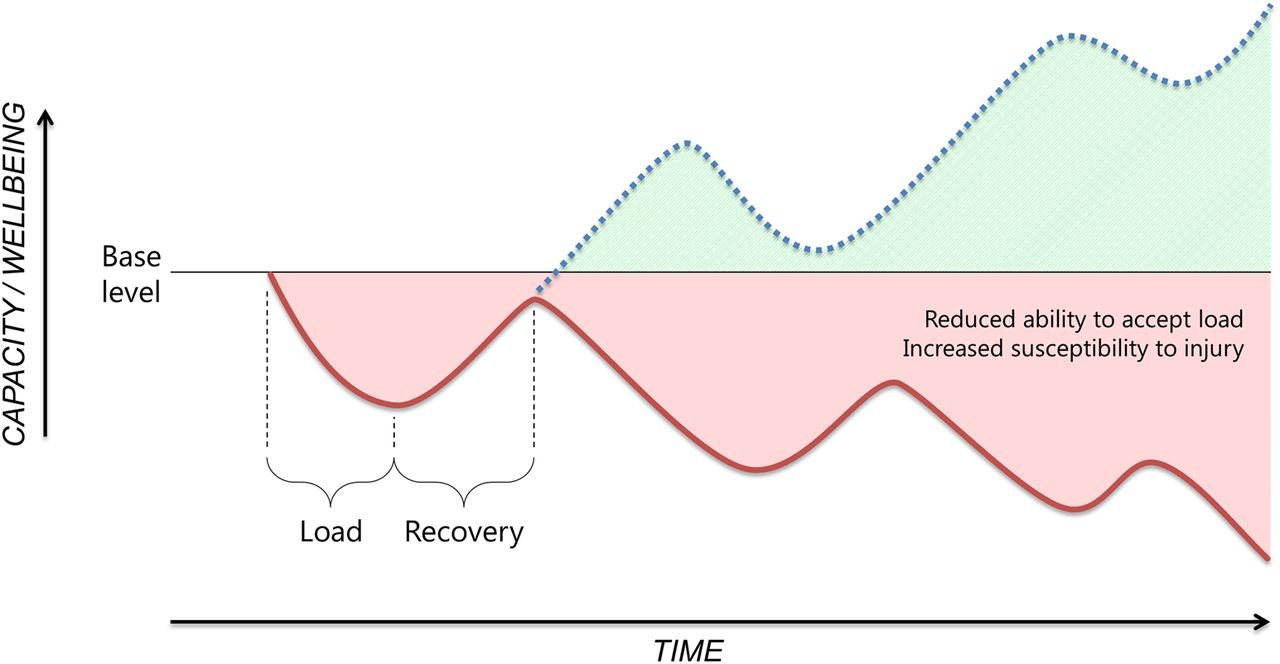

Improper loading

Not pretty, right? Instead of following the possible path above “base level,” this athlete trends further and further down on the capacity and well-being axis, first experiencing injury, then depression and mental health issues. Don’t become that athlete! Build your volume slowly from week to week, never increasing the current week volume or mileage more than 10% above the previous week. If you use fancy metrics such as CTL and ATL, never let ATL become 130% of CTL, provided you’ve given the athlete about four to six weeks of baseline training to allow your statistics to stabilize.

What about low volume? Why does that play a role in injury? Well, imagine an athlete who only runs about once a week—in this case, you’re not stressing the tissues enough for them to adapt. If the athlete simply keeps running once a week, she’ll never adapt, and eventually even that low load will cause an injury. Running does improve durability of your bones and joints, but you have to stress them to some degree to achieve that development.

What Should I Do?

First of all, get help. Find providers and coaches who can give you a bike fit, run form analysis, and swim stroke analysis every 12-18 months. You need to know about the dysfunctional movement patterns you display, so you can fix them before they become problematic.

Second? As you build to your competitive season, build slowly, sticking to no more than a 10% increase in load from week to week. Most of the literature suggests that 8-10 hours of cycling and running (total, not each) sits at a sweet spot in injury prevention. Many triathletes would do very well on six-to-seven hours of cycling, three-to-four of running, and three of swimming each week (swim volume hasn’t been found to increase the risk of injury, but technique issues definitely increase your risk exposure).

Finally, if you do get injured, absolutely crush your rehabilitation program, prioritizing your physical therapy exercises over your everyday training.