How to Start Swimming for Triathlon

Five Principles to Begin Your In-Water Career

Image courtesy of Dylan Haskin

We can’t tell you the number of times we’ve heard an athlete say “I’d be fine for the bike and run for a triathlon, but I haven’t swam since I was a kid, and I’m really nervous about signing up because of that.” First of all, good job for acknowledging your apprehension. Swimming carries the distinction of being both risky and technical, and therefore threatens both your ego and your physical well-being.

But you’re different. You’ve persevered, and here you are, standing on the pool deck, cold and wet from the demeaning shower the lifeguards forced you to take before diving in. You’ve watched some YouTube videos of questionable utility, and you’ve watched Kona like, a million times. You’ve got this, right? Again, we’d love to applaud your gusto, but let’s cover some basics before you jump in and start flailing around. Taking the time to nail your swim fundamentals will result in less wasted time in the pool. Since you’re a triathlete you don’t have too much in the way of time.

Image courtesy of Swim in Common

Water in front to water behind

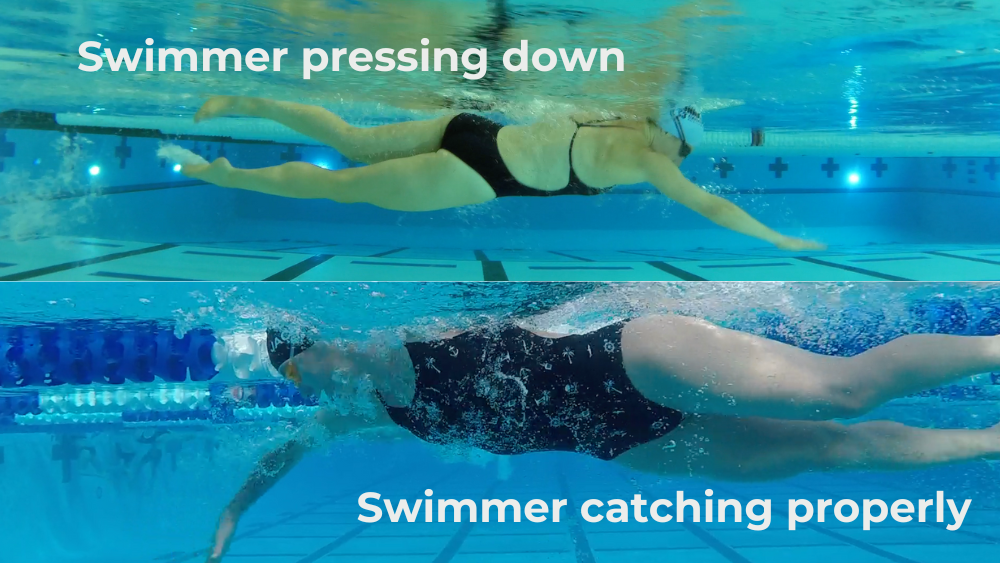

Understanding the goal of any movement carries you a long way towards success. Many adult-onset swimmers (our term for you for the rest of this piece) aren’t even sure of what moves a human body through the water: should I kick harder? When do I breathe? What’s this I keep hearing about an “S-Curve?” The answer, thankfully, is simple: in order to move forward through the water, you want to grab water with your palm and forearm and use your grip on that water to pull yourself forward. If you were playing tug-of-war, you’d pull in a straight line, right? The same idea holds true for swimming. You should remember, though, that water isn’t solid (otherwise, swimming would be impossible; go and try to swim on the surface of a frozen lake and tell us how it goes). Since water isn’t solid, no matter how good you are at grabbing it, your hand will slip through the water to some degree. The process of improving as a swimmer is learning how to “hold” more water and to diminish that amount of “slip.” So here is your first visualization: we “hold” water with the palm of our hand and, to a more limited degree, with our forearm. Our goal as swimmers is to get the hand and forearm vertical as soon as possible (i.e. pointing at the bottom of the pool). The sooner we can get the hand and forearm vertical (this concept is called “early vertical forearm”), the more water you can exert forward-moving force on.

In the picture above, you can see one swimmer who is pressing water down, rather than behind, and in the second picture you see that the elbow is bent and the forearm and hand are facing behind him/her. That’s the image you are trying to achieve. Now, before you even get in the water, we want you to practice “swimming” above the water. Try it right now, even. Your lead hand should angle slightly down into the “water,” the tip of the middle finger touching first. As soon as the hand enters the water, bend your wrist so your palm faces behind you. As soon as you’ve done that, bend your elbow to achieve that early vertical forearm. Practice this motion in short sets of 60 seconds before you ever even get in the water, to ingrain the most important thing you’ll be doing. Bonus? Practice this early vertical forearm (usually called the “catch” phase of the stroke) with stretch cords to build some strength and muscle memory around the movement.

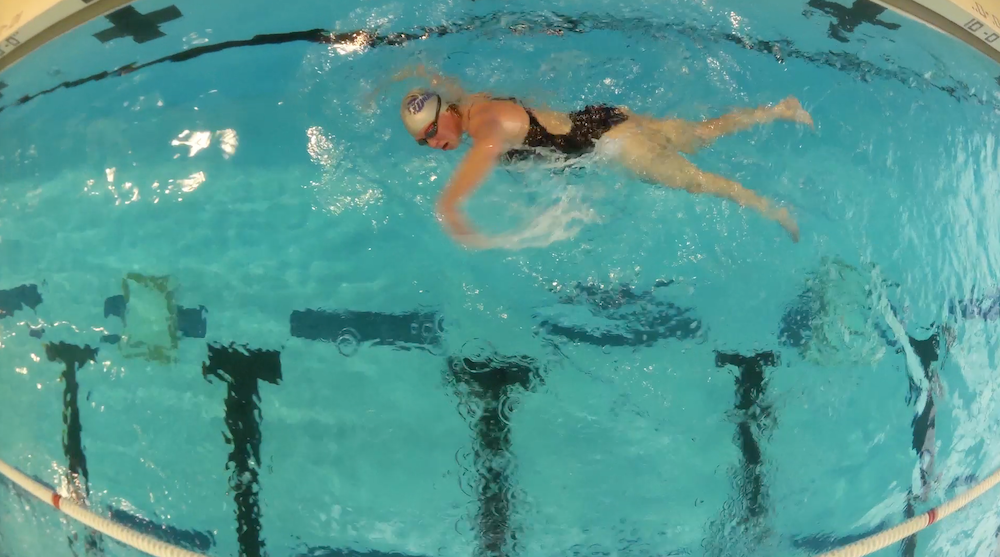

This swimmer is over-rotating. Do you see the ceiling or sky when you swim? You are probably over-rotating.

Whatever is going wrong, it’s going wrong when you breathe

One of the reasons we try to groove the stroke before you get into the water is that once you do take the plunge, most of your attention will focus elsewhere: staying alive! Yes, swimming is dangerous and drowning is something that can happen; we should all be clear-eyed about the dangers inherent in any activity. Of course, your body already knows this, and when you start swimming you’re likely to experience some panicky sensations. We all know what happens when we panicked: breathing tightens up. If you’re tight and not breathing, your stroke will definitely be affected. Think about it this way: would you hold your breath ever while running or cycling? Here is a short list of things that can happen to your stroke if you’re not breathing effectively:

Lifting your head to breathe -> hips and legs sinking behind you

Holding breath while head is underwater -> chest too buoyant and hips and legs sinking behind you

Holding breath while head is underwater -> needing more time while head is above water to exhale AND inhale = stroke slowing down too much/losing propulsion

Breathing only to one side -> losing balance, power, and proper rotation on the other side

This is a short, basic list, but it’s what we see the most of when bringing new swimmers to the pool. So how do you combat it? With the first drill you’ll perform actually in the water, the Sinkdown Drill. How do you do it? Head to the deep end of the pool (if you don’t have a deep end, no worries—we’ll give you an adjustment) and float vertically, feet pointing towards the bottom of the pool. When you’re ready, allow yourself to go under the water, clasp your arms to your sides (like doing a pencil dive), and begin exhaling the air out of your lungs in as relaxed a manner as possible. Allow yourself to sink to the bottom of the pool. See if you can hang out down there, emptying your lungs of air while remaining relaxed. Your ability to nail this drill now will improve your swimming later, we promise. Do five-to-ten sinkdowns at the start of each swim, so you can play around with your body’s buoyancy and learn how to make exhaling second nature. If you don’t have a deep end, don’t fret! Simply tuck your legs up to your chest like you’re doing a cannonball and perform the same drill.

kicking more won’t save you

Coming from sports that utilize the legs for propulsion, many new swimmers try to kick their way through swim workouts and find a small amount of success right off the bat. Sadly, that success is short-lived, and these swimmers end up on a performance plateau. Sprinters (and most of the swimmers you are likely to have seen in The Olympics) kick very hard, since their events finish in seconds, not minutes. Even the swimmers who compete in longer events kick quite a bit, but remember that the swimmers you see on television train, on average, 1200-1400 hours per year. They have massive aerobic engines, and kicking mobilizes some of the biggest muscle groups in your body. Takeaway? If you kick too hard, you’re going to run out of oxygen to fuel the muscles that actually move you through the water, your lats and shoulders. Focus on developing a small kick that works to hold your legs horizontal behind you. Throw on some fins and do some kick sets, either on your back or on your side, aiming to “shrink the kick” so you only use a light flutter with a straight leg. If you’re doing it right, you’ll feel fatigue in your glutes (your butt). If you’re bending your knee, you’ll feel fatigue in your quadriceps, which is not what we’re after. Watch the video below (courtesy of Swim in Common) for a primer on kicking too hard.

Your body provides the resistance

You may have heard the phrase “you can’t fire a cannon out of a canoe” somewhere in your world, whether you come from a nautical/camping background or not. The saying always begs the reply “Well, sure you can fire a cannon out of a canoe,” but the point that’s trying to be expressed here is that discharging a large force from a weak vessel will result in disaster (or, at the very least, a damaged canoe). While swimming, the most solid object or surface is...you. When you run, you press on the ground, which is very solid. You won’t lose too much force into the planet; you get a good forward return on the force you put behind you. In the water, we can’t count on the surface to provide reactionary forces to drive us forward: we have to be responsible for stiffening the canoe so that any force we get back from the water actually results in forward motion. The takeaway here? Well, first of all, keep doing your core exercises! Those are a huge part of any athlete’s success, and having a strong core will make you better at all of your endeavors. But in terms of active things you can do while swimming, concentrate on keeping your core taut and engaged. That doesn’t mean you have to flex and constrict your body, but lightly squeeze your core and glutes (your abs and butt!), and try to extend forward with good underwater posture, just the way your mom always told you to. You won’t remember to do this all the time, but see if you can remember to do it more often, and observe how much better you feel when you do so.

beware dogmatic advice, especially around stroke rate

For ages, swim coaches looked at successful swimmers and then tried to take their strokes and apply them to their less successful swimmers. While well-intentioned, this approach has had far-reaching consequences. The “successful stroke” of much of the last half-century of swimming has been the classic “long and glidey” stoke of swimmers such as Ian Thorpe and Michael Phelps. We won’t even touch the incorrect use of the word “glide” in all of this (that’s for another day), but the end result was swim coaches everywhere trying to impose the idea that “fewer strokes is always better.” This overriding philosophy led to a great number of frustrated and disenchanted swimmers who would be better served by a higher number of strokes per minute (or per length). If you bump into these kinds of directives out there, take them with a large crystal of salt, and instead experiment with different stroke rates that might work for you. Using a tool such as the Finis Tempo Trainer can help quite a bit with this experimentation, and it’s a tool that belongs in every athlete’s swim bag. On the other hand, many beginning swimmers do in fact take too many strokes per minute, as they flail away at the water ineffectively. Those athletes may respond to subtracting some strokes, but it is far more likely that they will see their stroke rate decrease as their stroke becomes more effective. Targeting your specific limiters in the water is the best way to see progress. The big takeaway here is to recognize when the coaches around you are being dogmatic, instead of considering the swimmer in front of them: YOU.

So that is it! We recognize that that’s still a lot of words, but swimming is a technical sport, and it rewards getting the theory correct before putting it into practice. Once you begin to adopt swimming, you may find a sport for life. Welcome to the open water!